7-11 CLERK: lovely day outside, isn’t it

ME: uhhh

ME INTERNALLY: shit. I didn’t notice. How do I continue this conversation

MY INNER MONOLOGUE: Service workers love it when you tell them the things mortal men were not meant to know, when you speak to them of principalities and powers upon the earth

ME: In the sun a wheel, in the wheel another wheel. Do you see?

7-11 CLERK: Yes, I see!

ME: For each turn of the outer wheel, one thousandth a turn of the inner wheel. And within the inner wheel a point of perfect darkness

7-11 CLERK: Right, growing, devouring. The death of all light

ME: Wanes the light - right - wanes the light and waxes the solar eye. Wanes the day of flesh and blood and waxes the night of crawling beasts. Chewing and swallowing. The name of the night to come is khoshek ha-gibbor

7-11 CLERK: Is that hot dog a quarter pound big bite or a spicy bite. They’re priced different

ME: Which one is cheaper

A few years ago, a group of friends persuaded me to join them in buying a cask of whisky. It was a fun day out. We headed to the distillery, a new one in the English countryside making a name for itself disrupting Scottish domination of the market, and took turns filling a 200 litre American oak barrel. The up-front cost was a few thousand pounds, which may not seem like much, but there was a catch.

First, whisky is not whisky until it has sat in a barrel for three years. We agreed to wait ten, which means those few thousand pounds would be tied up for a long time without a return.

Second, significant additional costs would be incurred before we could ever drink the whisky. At the end of the ageing process, we’d need to bottle it and label it, and pay excise duties and taxes. Assuming we maintained the whisky at cask strength, our barrel would yield around 260 bottles (there is a bit of evaporation along the way – the ‘angel’s share’ as it is known). At £8.50 per bottle to package it, plus excise duty of £31.64 per litre of alcohol (both of which are higher now than when we laid down the barrel) we’d have to stump up an additional £7,300 or so, after tax, before we could savour a dram.

But the benefits! All-in, we would be locking in a delightful whisky at a price of around £40 per bottle. The spirit (as whisky is known before it becomes whisky) has a light, fruity character highly rated by critics; the flavoursome notes delivered by the first-fill ex-Bourbon barrel promise to transform it into an exciting single malt. If it retails at £100 a bottle, we’ve got ourselves a bargain.

Along the way, we are welcome to visit our cask at the distillery’s bonded warehouse and once a year we are entitled to draw a 100ml sample to taste. If we can’t afford the outlay at the end of the contract, the distillery offers an interesting deal: It will pay all the duties and do all the bottling for us in exchange for two-thirds of the product. So there’s an option to sell at the end, albeit at a below-market rate.

The conditions of ownership are strict. Although we can share the cask, the distillery requires a single one of us to act as legal owner. That’s because it’s selling a product, not shares. It’s an important point; in the past, similar structures have fallen foul of the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) – there’s a fine line between owning whisky and owning some abstraction of whisky and the distinction has legal ramifications.

In 1971, officials at the Securities and Exchange Commission came across a series of adverts placed in newspapers across Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Florida. “Exceptional Capital Growth Is Possible When You Buy Scotch Whisky Reserves By The Barrel,” they read. The ads were placed by Maurice Lundy of Rhode Island whose business sold warehouse receipts on whisky to interested investors. “The principle of whisky lying in bond in Scotland is that the older the whisky the more the price appreciates,” his marketing materials proclaimed.

Although investors could in theory take delivery of the scotch, an SEC investigation concluded that “the steps required for the taking of physical possession of such whisky represented by said receipts are both difficult and unprofitable.” Only one investor had ever inquired as to the possibility of taking possession of the whisky and none had ever gone through with it.

In the eyes of the SEC, Lundy wasn’t selling whisky, he was selling whisky securities. And because he hadn’t registered his whisky securities, he was in violation of a whole set of rules that govern the issuance of securities. Lundy countered, of course, attempting to frame his receipts as anything but securities. But the US District Court in Rhode Island came down in favour of the SEC.

In doing so, it reached back to an earlier case heard by the Supreme Court in 1946. The case, SEC v. W.J. Howey Co., established a “test” of whether something is a security and therefore whether it falls within the purview of securities regulation (emphasis added):

The test of whether there is an “investment contract” under the Securities Act is whether the scheme involves an investment of money in a common enterprise with profits to come solely from the efforts of others; and, if that test be satisfied, it is immaterial whether the enterprise is speculative or non speculative, or whether there is a sale of property with or without intrinsic value.

The test derived from an investment contract as funky as a whisky receipt.

William John Howey was a successful real estate developer based in Florida. In 1914, he began buying land in Lake County for $8 to $10 an acre which he cleared and planted with citrus trees. Howey kept some of the citrus groves for his own use and sold off the rest.

By the early 1940s, his company was able to sell land planted with two year old trees for $750 an acre. But as part of the sale, it would offer to lease back the land via a service contract which gave the company the right to work the land and market the produce. Attracted by the promise of returns of 10% a year for ten years and the hospitality they enjoyed at a company-owned resort hotel, investors piled in: around 85% of the acreage sold was leased back. In theory, buyers could have farmed the citrus groves themselves, but most lacked the agricultural skills to do so.

As in its whisky case later, the SEC contended that the service contracts constituted securities and, as no registration statement had been filed, Howey’s company was in violation of securities laws. This one went all the way up to the Supreme Court with the SEC coming out victorious.

Over the years, other esoteric assets have been scrutinised under the Howey test. In the late 1960s, Colorado-based Continental Marketing Corporation sold live beavers to buyers across America. Over a short period of time, the company made over two hundred sales in sixteen states, grossing over a million dollars. By itself, weird but not untoward.

“Manifestly, the simple sale and delivery of live beavers do not, when viewed in isolation, constitute the sale of a security under the Act,” records the case the SEC brought against Continental Marketing Corporation in 1967.

But buyers were given a choice. They could care for their own animals, with each pair of beavers requiring a private swimming pool, patio, den and nesting box together with the services of a veterinarian, dental technician and breeding specialist. Or, at a cost of $6 per month per animal, they could place their beavers with a professional rancher connected with the company. Every single customer chose the latter. It was this that piqued the interest of the SEC. It seems that buyers were motivated less by a fondness for beavers and more by “an opportunity to share in the profits of the breeding stock stage…the most lucrative stage in the development of the beaver industry.”

Applying the Howey test, the District Court in Utah sided with the SEC. “Investment by members of the public was a profit-making venture in a common enterprise, the success of which was inescapably tied to the efforts of the ranchers and the other defendants and not to the efforts of the investors.”

Buying beavers became less fashionable after Continental Marketing Corporation lost its case; buying whisky, however, remained popular. Even after the US District Court of Rhode Island held whisky interests to be securities, the SEC noted “a substantial rise in the number of sales of whisky interests in this country.” It cautioned people who were solicited to invest in such securities to insist on a prospectus first.

The authority of the SEC derives from the Securities Act of 1933, sometimes referred to as the “truth in securities” law. The objective of the law is to protect investors by imposing a certain level of disclosure on issuers and outlawing deceit and misrepresentation. To accomplish this, the SEC requires all securities to be registered. Hence the need for a Howey test – it’s not always obvious what a security is.

Fifty years later, the SEC is waging the same war. The front isn’t whisky, citrus groves or beavers this time; rather, it’s crypto. Commissioners of the SEC have long held the view that crypto assets are securities. Current chair Gary Gensler said in a speech last year, “My predecessor Jay Clayton said it, and I will reiterate it: Without prejudging any one token, most crypto tokens are investment contracts under the Howey Test.”

Over the past several years, the SEC has gone after individual crypto projects. In total, it has accused 54 crypto assets of being securities. But there are around 25,500 crypto assets in existence, so even though the focus has been on large ones – covering around 10% of the market – it’s a painful process.

This week, the SEC changed course. In separate cases against crypto exchanges Binance and Coinbase, it added 16 more digital assets to its list of likely securities but rather than going after them, it went after the exchanges that provide a venue for them to trade. “The crypto assets it [Coinbase] has made available for trading…have included crypto asset securities, thus bringing Coinbase’s operations squarely within the purview of the securities laws.” By not registering as an exchange or broker, Coinbase is deemed in violation of such laws.

Coinbase was always cognisant of the risk. When it registered its own securities ahead of a Nasdaq listing two years ago, its disclosures stated:

We have policies and procedures to analyze whether each crypto asset that we seek to facilitate trading on our platform could be deemed to be a “security” under applicable laws… Regardless of our conclusions, we could be subject to legal or regulatory action in the event the SEC, a foreign regulatory authority, or a court were to determine that a supported crypto asset…is a “security” under applicable laws.

[W]e could be subject to judicial or administrative sanctions for failing to offer or sell the crypto asset in compliance with the registration requirements, or for acting as a broker, dealer, or national securities exchange without appropriate registration. Such an action could result in injunctions, cease and desist orders, as well as civil monetary penalties, fines, and disgorgement, criminal liability, and reputational harm.

But then they also stated that “many of our employees and service providers are accustomed to working at tech companies which generally do not maintain the same compliance customs and rules as financial services firms. This can lead to high risk of confusion…” So who knows?

If it loses its case, it’s bad news for Coinbase. In the first quarter of this year, 46% of the company’s transaction revenues came from crypto assets other than Bitcoin and Ethereum (Gary Gensler recognises that Bitcoin is not a security), equivalent to 22% of total revenues.

In addition, The SEC targets the company’s “staking” program, in which investors’ crypto assets are transferred to and pooled by Coinbase and subsequently “staked” (or committed) in exchange for rewards, which Coinbase distributes pro-rata to investors after paying itself a commission. The SEC deems the staking program to be an offer of securities – another violation. In the first quarter, 10% of the company’s total revenues came from staking. In combination, 32% of Coinbase revenues are at risk, which could be closer to two-thirds of earnings given the higher margins on these revenue lines.

Coinbase could always register with the SEC of course, but it’s not easy. Few crypto firms have been successful. So it’s fighting:

Coinbase’s position is that the Howey test does not apply to secondary market trading. “Howey is inapposite to the secondary market trading of digital assets,” it declares. It seems a bit of a stretch to suppose that once something is a security it’s not always a security, but I’m no lawyer. And as for the SEC’s claim that staking constitutes an offering of securities, Coinbase argues that the program fails to meet the threshold of the Howey test along each of its dimensions: investment of money, common enterprise, and profits coming solely from the efforts of others.

As Howey did all those years ago, Coinbase has threatened to take this case all the way to the Supreme Court. But another case may set a precedent. In December 2020, the SEC filed an action against Ripple Labs, alleging that it raised over $1.38 billion through an unregistered securities offering of its digital asset XRP. Ripple was launched in 2012 as a system to facilitate cross-border financial transactions – “a replacement for SWIFT” – and XRP is the token it uses for payments. The company maintains that XRP is not a security and has said it will spend $200 million on its defence.

As in its Coinbase case, the SEC leans heavily on Howey. It notes that although the Howey case was a long time ago, the Supreme Court made clear that the definition of whether an instrument is an investment contract and therefore a security is a “flexible rather than a static principle, one that is capable of adaptation to meet the countless and variable schemes devised by those who seek the use of the money of others on the promise of profits.”

Ripple’s claim is that XRP doesn’t pass the test. It takes each of its dimensions in turn:

For the SEC to prevail in its opposition, the Court would have to endorse the SEC’s theory that there can be an “investment contract” without any contract, without any investor rights, and without any issuer obligations. It would have to endorse the SEC’s theory that there can be a “common enterprise” even if the SEC can not say what the enterprise is or prove any of the elements that define such enterprises. And it would have to endorse the SEC’s theory that purchasers could reasonably have expected profits from Ripple’s efforts even though Ripple never promised to make any efforts, even though it expressly disavowed any obligation to do so, and even though profits were overwhelmingly due not to Ripple’s efforts, but to market forces.

…The SEC’s position boils down to a view that any time someone buys an asset hoping to make money, and the seller’s interests are even partly aligned with the buyer’s, it is a security subject to registration. That is not the law, even if the seller uses the sales proceeds to run its business. If Congress wants to expand the securities laws that way, it can do so; but this Court should not.

The future of crypto in America may yet be decided by Congress, but failing that it will be up to the courts to determine whether a 75+ year old test is as pertinent today as it was when it was devised. Coinbase is ready for the fight. “I’m optimistic, and I think we hope we’re doing a service for the industry and for America here,” said CEO Brian Armstrong this week.

The only question for me is whether my whisky will be ready in time to toast the winner.

The ancient Romans were masters of engineering, constructing vast networks of roads, aqueducts, ports, and massive buildings, whose remains have survived for two millennia. Many of these structures were built with concrete: Rome’s famed Pantheon, which has the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome and was dedicated in A.D. 128, is still intact, and some ancient Roman aqueducts still deliver water to Rome today. Meanwhile, many modern concrete structures have crumbled after a few decades.

Researchers have spent decades trying to figure out the secret of this ultradurable ancient construction material, particularly in structures that endured especially harsh conditions, such as docks, sewers, and seawalls, or those constructed in seismically active locations.

Now, a team of investigators from MIT, Harvard University, and laboratories in Italy and Switzerland, has made progress in this field, discovering ancient concrete-manufacturing strategies that incorporated several key self-healing functionalities. The findings are published today in the journal Science Advances, in a paper by MIT professor of civil and environmental engineering Admir Masic, former doctoral student Linda Seymour ’14, PhD ’21, and four others.

For many years, researchers have assumed that the key to the ancient concrete’s durability was based on one ingredient: pozzolanic material such as volcanic ash from the area of Pozzuoli, on the Bay of Naples. This specific kind of ash was even shipped all across the vast Roman empire to be used in construction, and was described as a key ingredient for concrete in accounts by architects and historians at the time.

Under closer examination, these ancient samples also contain small, distinctive, millimeter-scale bright white mineral features, which have been long recognized as a ubiquitous component of Roman concretes. These white chunks, often referred to as “lime clasts,” originate from lime, another key component of the ancient concrete mix. “Ever since I first began working with ancient Roman concrete, I’ve always been fascinated by these features,” says Masic. “These are not found in modern concrete formulations, so why are they present in these ancient materials?”

Previously disregarded as merely evidence of sloppy mixing practices, or poor-quality raw materials, the new study suggests that these tiny lime clasts gave the concrete a previously unrecognized self-healing capability. “The idea that the presence of these lime clasts was simply attributed to low quality control always bothered me,” says Masic. “If the Romans put so much effort into making an outstanding construction material, following all of the detailed recipes that had been optimized over the course of many centuries, why would they put so little effort into ensuring the production of a well-mixed final product? There has to be more to this story.”

Upon further characterization of these lime clasts, using high-resolution multiscale imaging and chemical mapping techniques pioneered in Masic’s research lab, the researchers gained new insights into the potential functionality of these lime clasts.

Historically, it had been assumed that when lime was incorporated into Roman concrete, it was first combined with water to form a highly reactive paste-like material, in a process known as slaking. But this process alone could not account for the presence of the lime clasts. Masic wondered: “Was it possible that the Romans might have actually directly used lime in its more reactive form, known as quicklime?”

Studying samples of this ancient concrete, he and his team determined that the white inclusions were, indeed, made out of various forms of calcium carbonate. And spectroscopic examination provided clues that these had been formed at extreme temperatures, as would be expected from the exothermic reaction produced by using quicklime instead of, or in addition to, the slaked lime in the mixture. Hot mixing, the team has now concluded, was actually the key to the super-durable nature.

“The benefits of hot mixing are twofold,” Masic says. “First, when the overall concrete is heated to high temperatures, it allows chemistries that are not possible if you only used slaked lime, producing high-temperature-associated compounds that would not otherwise form. Second, this increased temperature significantly reduces curing and setting times since all the reactions are accelerated, allowing for much faster construction.”

During the hot mixing process, the lime clasts develop a characteristically brittle nanoparticulate architecture, creating an easily fractured and reactive calcium source, which, as the team proposed, could provide a critical self-healing functionality. As soon as tiny cracks start to form within the concrete, they can preferentially travel through the high-surface-area lime clasts. This material can then react with water, creating a calcium-saturated solution, which can recrystallize as calcium carbonate and quickly fill the crack, or react with pozzolanic materials to further strengthen the composite material. These reactions take place spontaneously and therefore automatically heal the cracks before they spread. Previous support for this hypothesis was found through the examination of other Roman concrete samples that exhibited calcite-filled cracks.

To prove that this was indeed the mechanism responsible for the durability of the Roman concrete, the team produced samples of hot-mixed concrete that incorporated both ancient and modern formulations, deliberately cracked them, and then ran water through the cracks. Sure enough: Within two weeks the cracks had completely healed and the water could no longer flow. An identical chunk of concrete made without quicklime never healed, and the water just kept flowing through the sample. As a result of these successful tests, the team is working to commercialize this modified cement material.

“It’s exciting to think about how these more durable concrete formulations could expand not only the service life of these materials, but also how it could improve the durability of 3D-printed concrete formulations,” says Masic.

Through the extended functional lifespan and the development of lighter-weight concrete forms, he hopes that these efforts could help reduce the environmental impact of cement production, which currently accounts for about 8 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Along with other new formulations, such as concrete that can actually absorb carbon dioxide from the air, another current research focus of the Masic lab, these improvements could help to reduce concrete’s global climate impact.

The research team included Janille Maragh at MIT, Paolo Sabatini at DMAT in Italy, Michel Di Tommaso at the Instituto Meccanica dei Materiali in Switzerland, and James Weaver at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University. The work was carried out with the assistance of the Archeological Museum of Priverno in Italy.

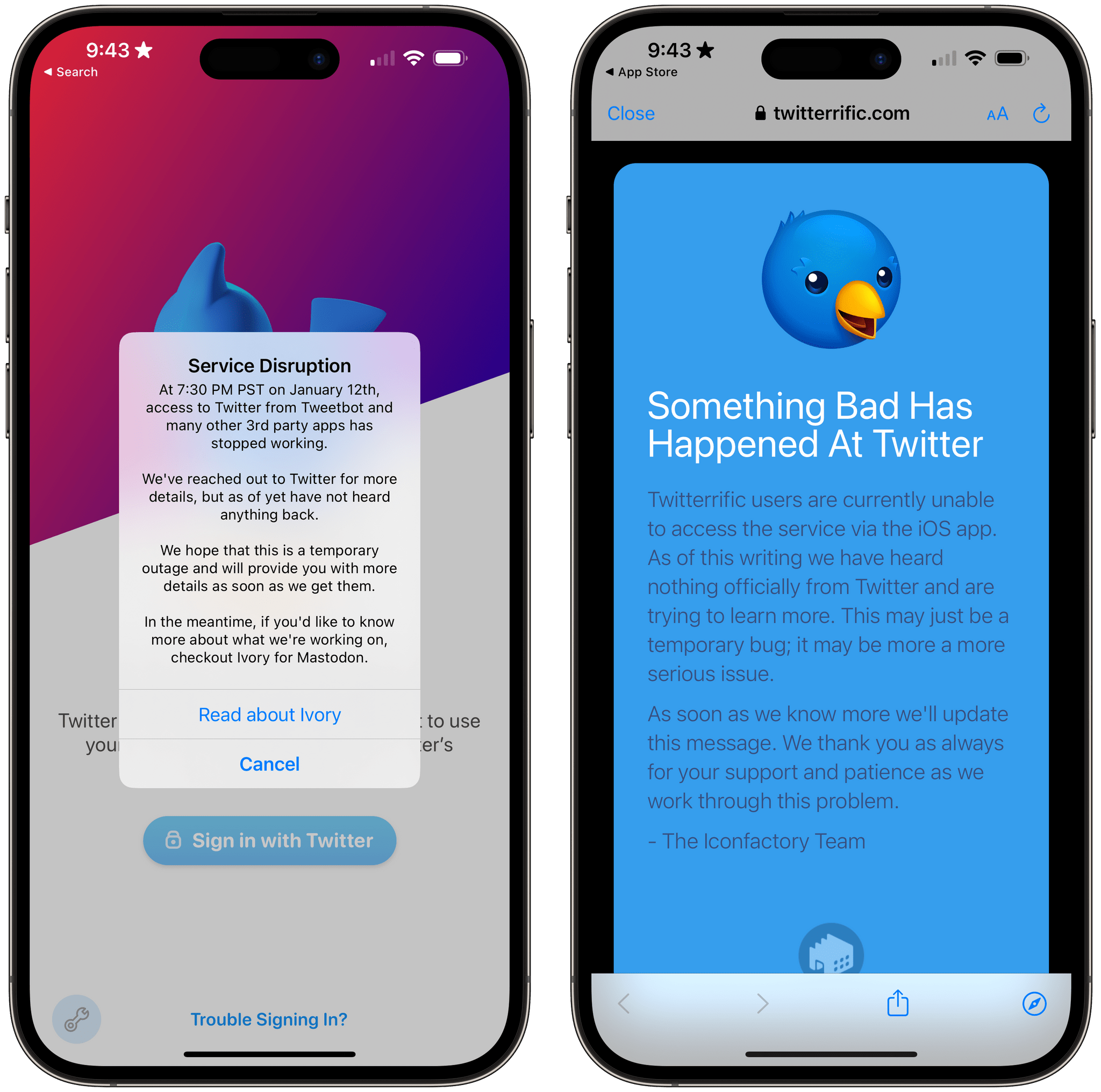

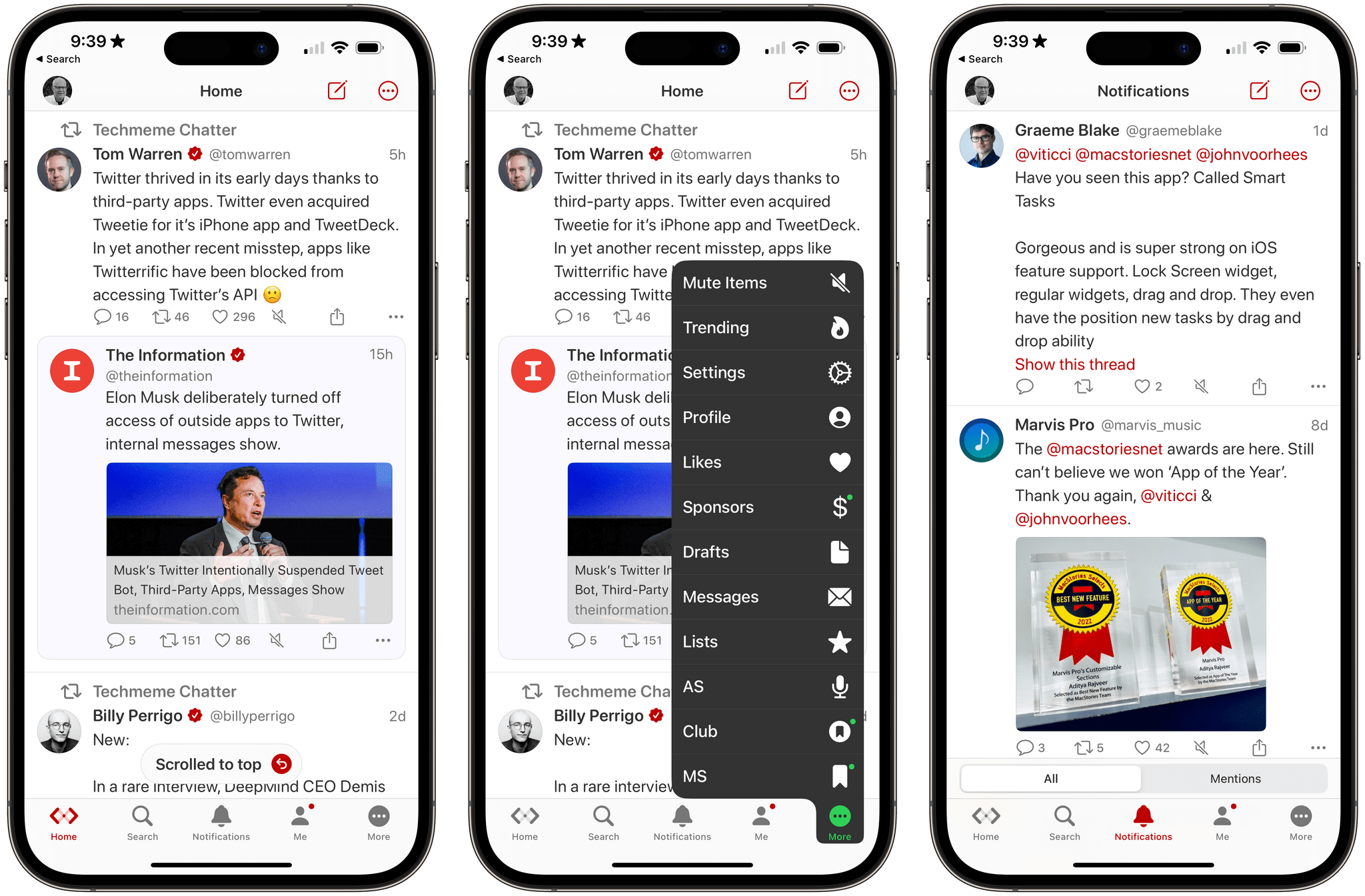

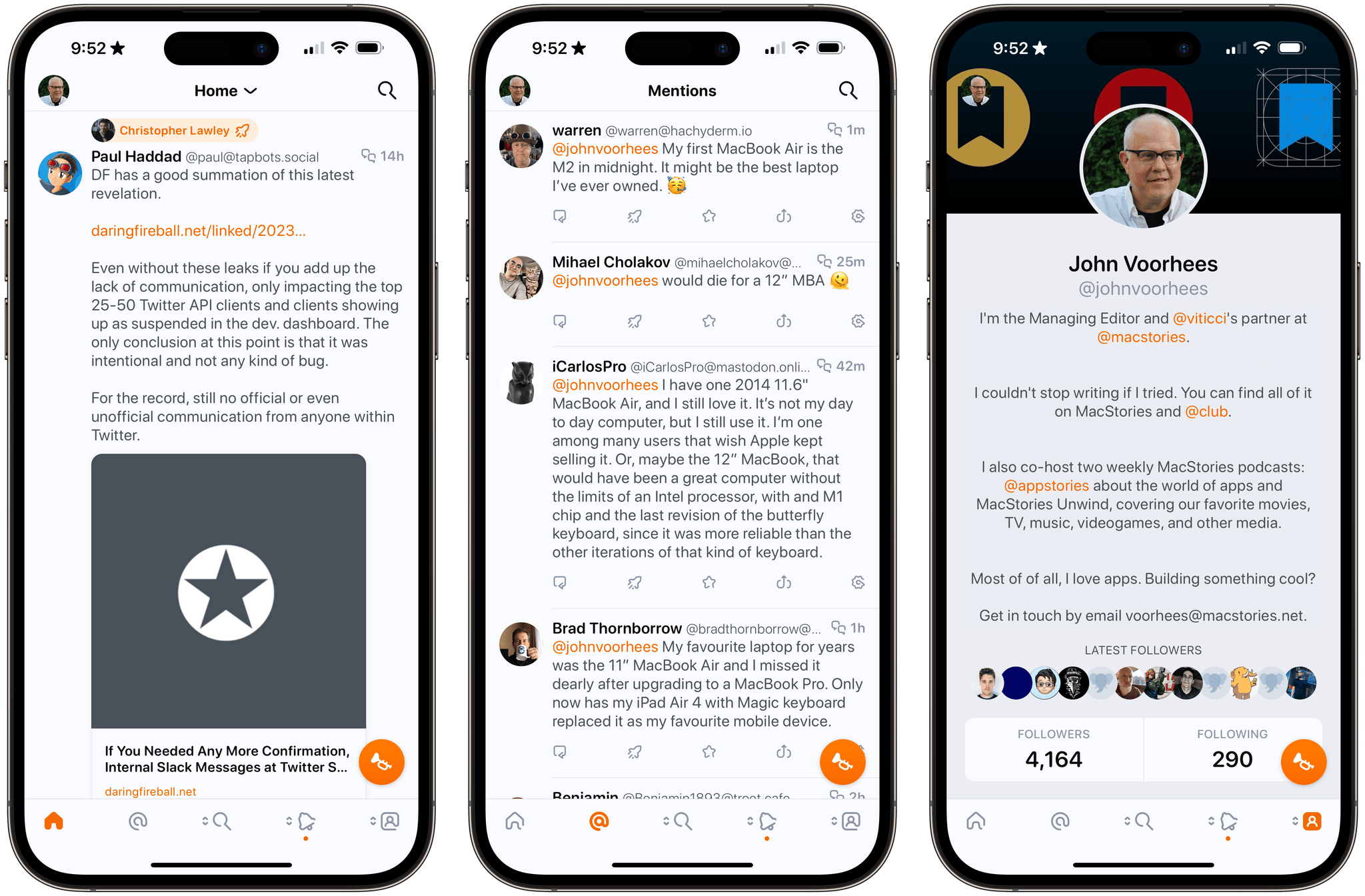

Late yesterday, The Information reported that it had seen internal Twitter Slack communications confirming that the company had intentionally cut off third-party Twitter app access to its APIs. The shut-down, which happened Thursday night US time, hasn’t affected all apps and services that use the API but instead appears targeted at the most popular third-party Twitter clients, including Tweetbot by Tapbots and Twitterrific by The Iconfactory. More than two days later, there’s still no official explanation from Twitter about why it chose to cut off access to its APIs with no warning whatsoever.

To say that Twitter’s actions are disgraceful is an understatement. Whether or not they comply with Twitter’s API terms of service, the lack of any advanced notice or explanation to developers is unprofessional and an unrecoverable breach of trust between it and its developers and users.

Twitter’s actions also show a total lack of respect for the role that third-party apps have played in the development and success of the service from its earliest days. Twitter was founded in 2006, but it wasn’t until the iPhone launched about a year later that it really took off, thanks to the developers who built the first mobile apps for the service.

Twitterrific’s website in 2009. Source: The Wayback Machine.

By 2007 when the iPhone launched, The Iconfactory’s Twitter client, Twitterrific, was already a hit on the Mac and had played a role in coining the term ‘tweet’. The app was first to use a bird icon and character counter too. And, although the iPhone SDK was still months off, The Iconfactory was already experimenting with bringing Twitterrific to the iPhone with the help of a jailbroken iPhone and class dumps of iPhone OS.

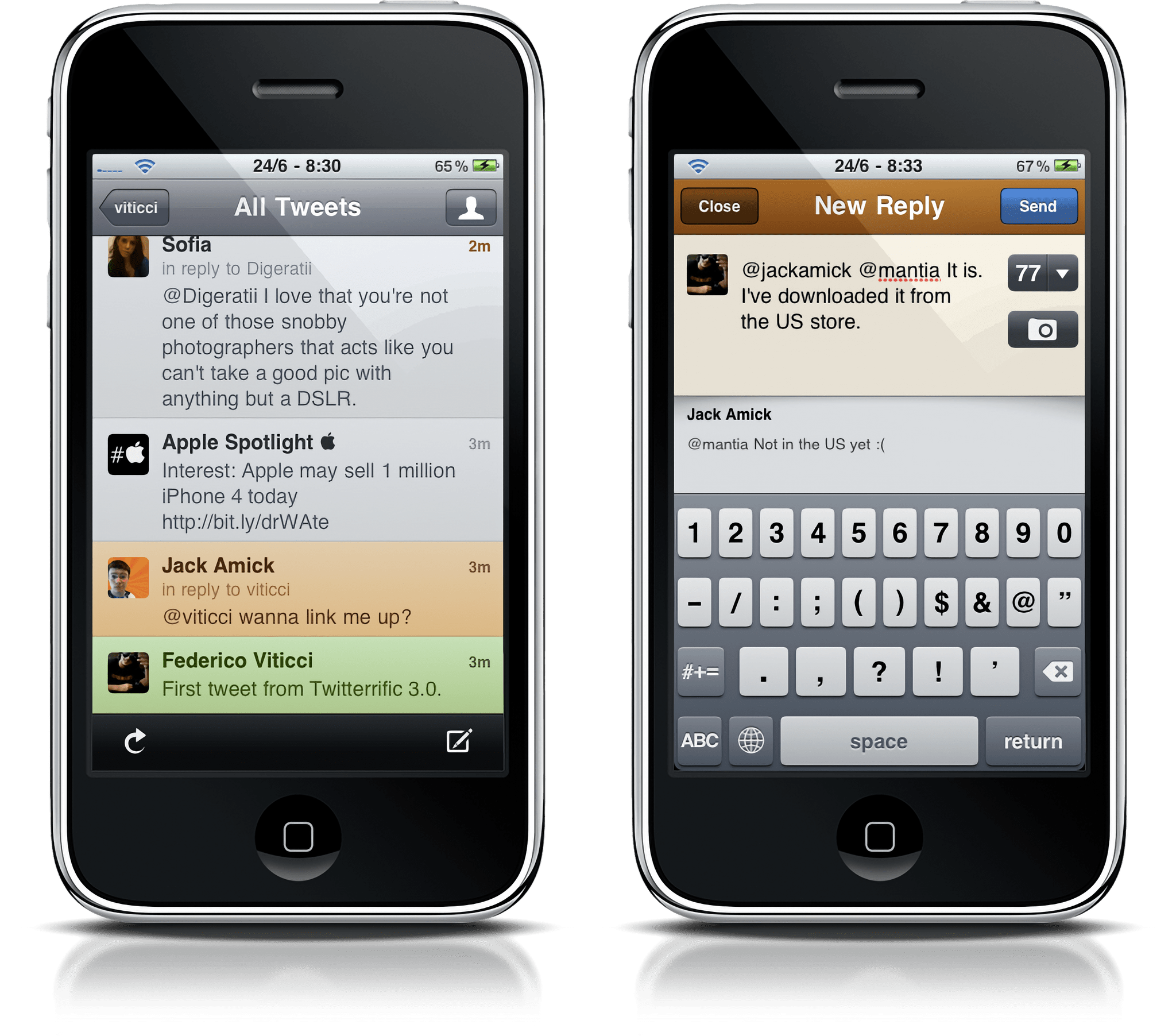

By the time Twitter bought Tweetie, Twitterrific was already on version 3.0.

Despite the popularity of the iPhone, Twitter didn’t build its own mobile app. Instead, the company purchased Loren Brichter’s Tweetie in 2010. Not only was Tweetie a beautifully designed app that performed better on early iPhones than many of its competitors, but it also introduced the world to ‘pull-to-refresh, a UI detail that was later folded into iOS itself. Twitter re-skinned Tweetie as the official Twitter app, followed up not long after by a flawed iPad app, and later, a Mac version in early 2011 that Brichter had been working on at the time of the acquisition.

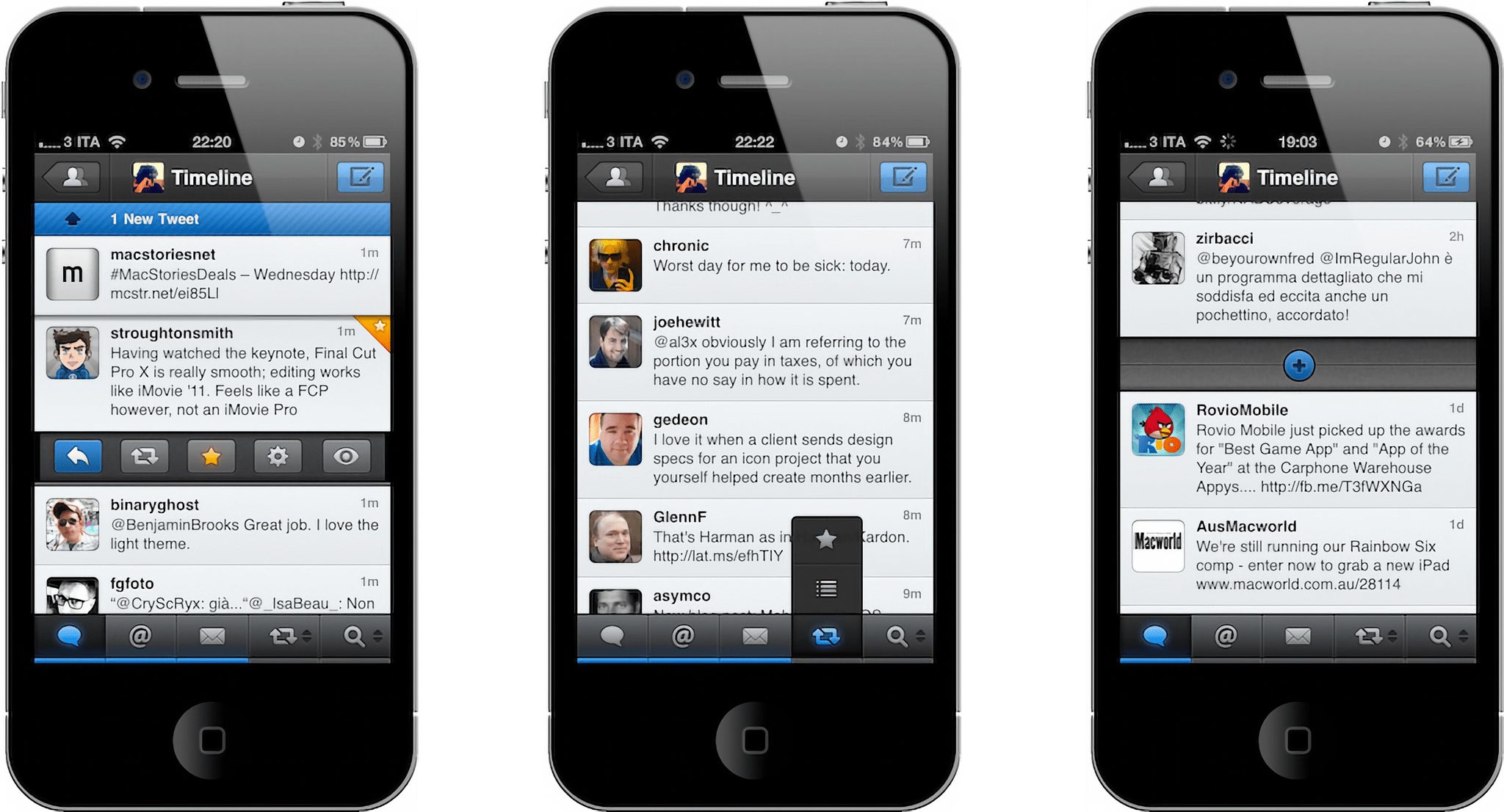

Tweetbot 1.0.

Even after Twitter had its own suite of apps, the third-party app market flourished. Tweetbot by Tapbots came along in 2011 and quickly became a favorite of many users, distinguishing itself with its steady stream of new power-user features and thoughtful design. But it wasn’t long before Twitter’s relationships with third-party developers began to sour. It started with a vague set of rules introduced in 2012 that preferred CRM and analytics apps over clients like Twitterrific and Tweetbot. The ups and downs over the years that followed are too numerous to count, but the consequence was that for many years few new Twitter clients were developed.

With the introduction of version 2.0 of its API, third-party Twitter apps, like Spring, gained new, innovative features.

However, relations began to thaw with the announcement of version 2.0 of the Twitter API, which went into effect in 2021. Not only did the API update make new features available, but Twitter promised to loosen restrictions on third-party developers. That led to renewed interest in third-party client development, resulting in innovative new features in apps like Spring, which was a runner-up in the Best App Update category of the 2022 MacStories Selects awards.

As it turns out, Twitter’s developer detente was short-lived. The fact that Elon Musk’s Twitter has cut off third-party developers isn’t surprising. Franky, I expected it sooner, but I didn’t expect it to be done with an utter lack of respect for the developers who played such a critical role in the service’s success for more than a decade. The number of people who use third-party Twitter apps may be small in comparison to the service’s overall user base, but the role of the developers of those apps and the value of those power-users to Twitter’s success is outsized by comparison. The developers of Twitterrific, Tweetbot, and every other app that has lost access to Twitter’s APIs deserved better than a silent flip of the switch late one Thursday night.

There have been many moments over the past decade when we worried that third-party Twitter apps might have met their end and didn’t. Unfortunately, I think this time, those past fears have been realized.

The MacStories team moved its social media presence to Mastodon in mid-December. So, if you’ve lost the use of your favorite third-party Twitter app and are looking for an alternative place to keep up on everything Apple, you can follow us there:

- MacStories Accounts

- MacStories Team Accounts.

Tapbots’ Ivory beta.

Also, Tweetbot users will be happy to know that Tapbots is working on a Mastodon client called Ivory that is currently in beta and should be released soon. We’ll have coverage of Ivory on MacStories as soon as it’s released publicly.

Support MacStories and Unlock Extras

Founded in 2015, Club MacStories has delivered exclusive content every week for over six years.

In that time, members have enjoyed nearly 400 weekly and monthly newsletters packed with more of your favorite MacStories writing as well as Club-only podcasts, eBooks, discounts on apps, icons, and services. Join today, and you’ll get everything new that we publish every week, plus access to our entire archive of back issues and downloadable perks.

The Club expanded in 2021 with Club MacStories+ and Club Premier. Club MacStories+ members enjoy even more exclusive stories, a vibrant Discord community, a rotating roster of app discounts, and more. And, with Club Premier, you get everything we offer at every Club level plus an extended, ad-free version of our podcast AppStories that is delivered early each week in high-bitrate audio.

Join NowScooter executives are bailing out.

It’s an experience familiar to many errant scooter riders: you’re barreling toward a red light and you’re tapping the brakes but they aren’t working, so it’s time to jump and let the scooter go flying.

Bird’s CEO and CFO have stepped down. I’ve learned Lime’s CFO is leaving.

Travis VanderZanden — the co-founder of Bird who reportedly cashed out tens of millions worth of stock during the company’s meteoric rise in valuation — has stepped down as the company’s leader. VanderZanden will remain chairman of the company’s board. Shane Torchiana, an obscure former BCG partner who has been at Bird since 2018, is taking over as president and CEO.

Bird’s Chief Financial Officer Yibo Ling — like VanderZanden a former Uber executive — is calling it quits.

Meanwhile, Andrea Ellis, who helped Lime raise $523 million in convertible debt and term loan financing late last year, is leaving Lime, sources told me and the company confirmed.

While Lime is well-capitalized after the debt financing last year, Bird appears to be in real peril. Bird’s market capitalization has fallen to $83.4 million. Embarrassingly, the company is in trouble with the New York Stock Exchange because its share price has fallen below the minimum price of $1.

Bird’s stock closed at $0.35 Thursday and had fallen two cents Friday morning.

As of June, Bird had $57 million in cash and cash equivalents. Meanwhile, the company burned through $47 million in net cash from operating activities in the first six months of the year. It doesn’t take higher level math skills to start to wonder whether Bird’s days are numbered.

Winter is coming. Literally. The scooter business is extremely seasonal.

I wanted to take a moment to eulogize the venture scale scooter business. We’re seeing the full unraveling of the blitz scale, cash-on-fire venture model.

This is probably the end — for this tech cycle at least — of the idea that if only venture capitalists can throw enough money at something, it will become a tech company. With Juicero, WeWork, Zume Pizza, Soylent, and so many others — companies were designated “tech” startups because venture capitalists invested in them. VCs forgot that things were supposed to flow the other way.

I’m not saying scooters are actually dead. Flying car company Kittyhawk — well, that’s dead (or about to be). And there will be many other cash intensive “tech” businesses that bite the dust. Bird could survive, I guess — or sell. Lime could end up being the last man standing — and monopoly pricing could suddenly seem a lot more attractive.

But I feel confident in declaring — after catching up with former scooter employees — that this is not a venture-style business that’s going to reap venture-sized returns.

Lime can’t even bullshit me that they’re profitable. The company told me in a statement that they’re working to “drive closer to profitability.” That’s adjusted EBITDA profits that they’re driving toward. Lime isn’t profitable even if you squint and juke the stats.

“We ran the test and it turns out people don’t ride scooters. That’s just the problem,” one former scooter employee commiserated to me.

Like many ideas that attract hordes of venture capital dollars, the intuition was compelling: cheaper batteries and Chinese manufacturing paired with cellphones could make scooters a better, more sustainable business model than ride sharing. It actually seemed good for the world.

One Bird investor tried to explain the early hype. Investors had salivated over Bird’s top-line growth, this person explained to me. “I do have a note that their weekly run rate (granted it is a highly seasonal business) was over $300m. Just sharing this because if you just followed the top line numbers (not the economics) it would make it one of the fastest consumer revenue stories in venture history. (And plenty of other investments like YouTube were wildly unprofitable and had tremendous product/market fit as well that did work out). Even Google — one of the fastest growing consumer businesses ever didn’t come out this hot.”

Valuations soared. Announced in February 2018, David Sacks led the Series A at Craft which valued Bird at $60 million post-money. Sequoia led a $150 million Series C investment in Bird that valued it at $1 billion in 2018 and then led another $158 million round that valued Bird at $2.1 billion, according to Pitchbook. It was a major investment for Roelof Botha who would go on to become Sequoia’s senior steward.

Sequoia had missed out on Uber. In 2018 Uber was going public, valued at $82 billion in the IPO. This was a chance to get it right the second time.

Uber wasn’t as big of a miss as Sequoia might have thought — it’s worth $57 billion today. Bird is worth $83.4 million.

Lime is a similar story. Uber has poured hundreds of millions into the company. GV led a $330 million round in 2018 that valued Lime at $1.1 billion. Since Lime is still a private company, we don’t know what it’s worth today.

“It was the beginning of that pure VC ‘herd mentality’ period,” remembers someone from the on-demand world. “Almost everyone was trying to tell everyone over and over the economics didn’t make any sense, but no reason for anyone to listen.”

Why did scooters fail to live up to the hype?